This is a story about how an experiment in the north of Ghana improved health and well-being in rural communities. How health staff in these remote areas have been working tirelessly to prevent the deaths of mothers and children. How a radical approach to health research, known as embedded research, has revolutionized how the government delivers health services under difficult circumstances.

What is the secret to Ghana’s success, and why are so many other countries interested in their approach?

Ghana’s success story

For over 20 years, Ghana’s CHPS programme has been the focus of the country’s primary health care strategy. It’s a community-centred approach that has transformed maternal and child health in the most inaccessible parts of the country. But how did it come into being, and what has Ghana done differently that has made it so successful?

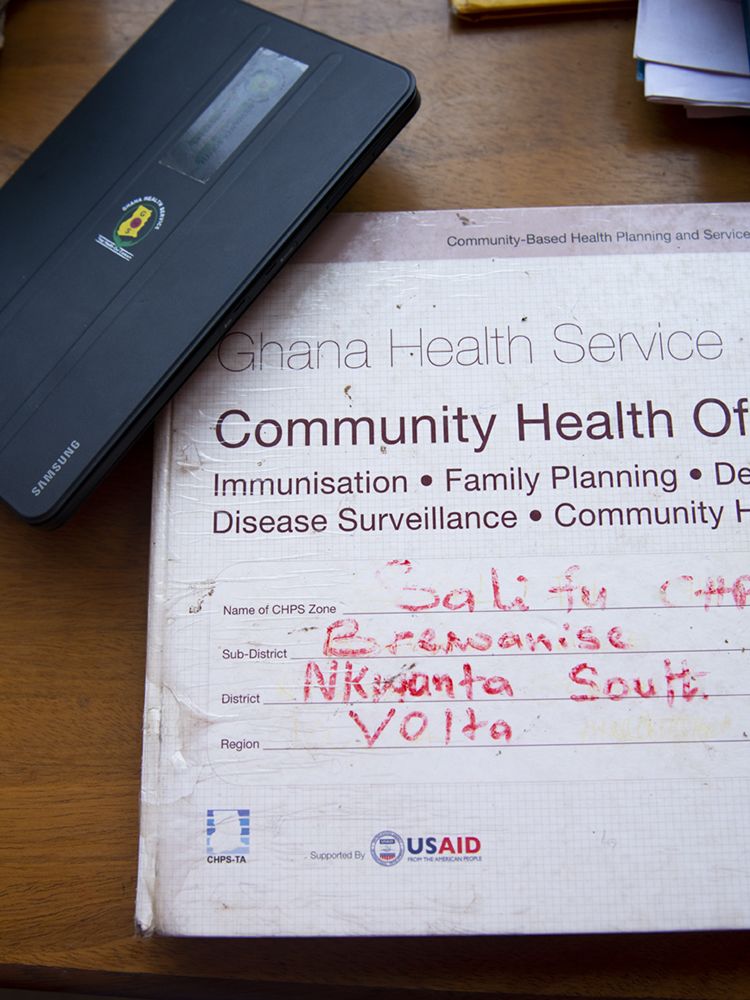

Community-based Health Planning and Services – more commonly referred to by its acronym, CHPS (pronounced ‘chips’) – is well known by health systems experts across the world. In rural areas, CHPS is often the first point of contact with government health services.

As in many other low- and middle-income countries, Ghana experiences a great number of impediments to improving health and well-being for its citizens. Many people live long distances from the nearest health centre. Access to electricity, mobile-cellular coverage and clean water are a challenge in rural areas. While international standards suggest that the ideal ratio is one doctor per 1,000 people, in Ghana in 2017 there was only one doctor per 8,098 people, and most of these doctors lived in cities and towns. In addition to logistical challenges, there are also local cultural beliefs preventing women from seeking care, even during childbirth.

In the face of these challenges, Ghana has innovated.

Good health begins in the community

Instead of placing all their investment in hospitals, Ghana has taken health to the heart of the village. Specially trained nurses known as Community Health Officers are posted to the rural areas - living in the heart of the community - so that they are available in the case of emergencies. Their job is to act as the frontline of the health system, supporting immunization, family planning and maternal and child health more generally. They are active in seeking out community members who are ill or otherwise in need, often travelling long distances to call on their clients.

Community members have been trained to assist the nurses as Community Health Volunteers. They use checklists and guides to structure their interactions as they go door to door checking on the health of their neighbours – particularly pregnant women and babies. They act as an interface between the community and the Ghana Health Service, communicating about health campaigns and events and supporting the health service to understand the needs of the people. Unpaid and yet unstinting, they labour year-on-year to help their communities thrive.

Active community health volunteers

Like many of the members of her small community in the Volta Region of Ghana, Ms Elizabeth Amenyo farms cassava for a living. As she conducts her household chores, bathing her children and sweeping the house, she explains the history of her own relationship with health services.

Earlier in life, Ms Amenyo was trained as a Traditional Birth Attendant by her mother, an occupation handed down through the generations. In the years before CHPS, access to government services was hampered by the large distances that women needed to travel to get care – the dusty, bumpy roads they had to ride for hours by motorbike to get to the nearest hospital.

In the absence of medical care, women like Ms Amenyo helped local women give birth at home, offering comfort and support. Being a Traditional Birth Attendant was a highly respected job, and families would show their gratitude by giving her gifts of food and other tokens of appreciation. But without access to trained health care professionals, many women died of preventable complications.

Ms Amenyo herself lost her first child to malaria when he was two years old. It was a turning point. It prompted her to become a Community Health Volunteer - for free - in the hope that others would not die needlessly.

Summing up the progress that has been made, Elizabeth explained:

"I wanted my community to progress. I love my community. We, the volunteers, work together with the nurses. There are no barriers - we are a team."

Embedded research - the secret to the success of CHPS

CHPS is unique in how it harnesses the expertise of policy-makers and health professionals alongside the energy and wisdom of the community to make changes that have a big impact. But it didn’t emerge by chance – its success rests on the expertise of academics who have played a major role since it was first conceived over 20 years ago in the Upper East Region.

Key to the success of the CHPS programme has been an innovative research approach known as embedded research.

Embedded research integrates research activities with existing health programmes and policies. Researchers engage with decision-makers and people who are delivering health services when setting research priorities, aligning research activities closely with the programmes they are intended to support.

This means research is more relevant to the problems being faced by health policy-makers and providers and the contexts they are working in. The data that is generated empowers them to make evidence-based decisions on the real-world challenges they face. Working as a team, embedded research projects are able to identify challenges, find the cause and test solutions during a programme's implementation.

But what does embedded research look like in practice? What were the practical steps Ghana took to implement this approach, and how did it contribute to the success of CHPS?

Embedded research in CHPS can be broken down into five steps.

Step 1

Believe in research

Trust in the power of research evidence. Ghana has a ‘learning health system’: research and routine data collected through health services play a large role in decision-making and identifying challenges. Through the creation of health research centres as a critical part of its health service and strong links with researchers working in its universities, it has embedded the use of evidence in decision-making about the way that services are delivered.

A new approach

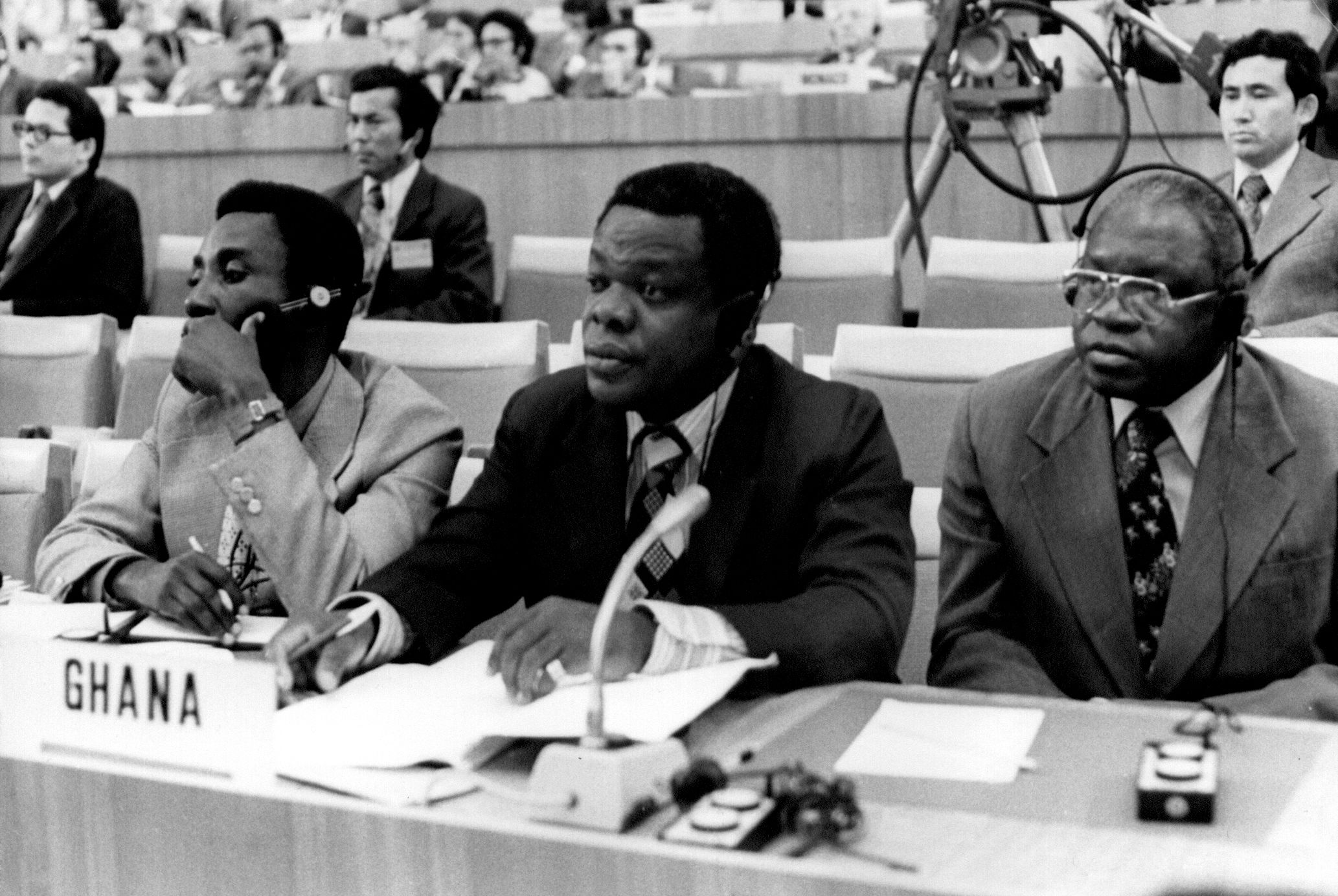

In 1978, the International Conference on Primary Health Care in Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan revolutionized the way that ill health was tackled.

The primary health care approach emphasized the role of communities in ministering to their members with a focus on preventing ill health, rather than curing people who are already sick. It focused on the point of a person’s first interaction with the health system and aimed to make that point as close to where people live and work as possible.

Development of the health sector in Ghana had tended to focus on cities and towns. Following independence in 1957, the government shifted focus to neglected rural areas and the north of the country to reach the poorest and most marginalized. Ghana needed to devise a health programme that catered to citizens living in the direst circumstances, that made the best use of the available resources. This was the genesis of CHPS.

The Navrongo experiment

Navrongo, in the north of Ghana, is home to one of the government’s three health research centres. Drawing on models of care that had been successful in other countries and extensive consultation with local communities, the Navrongo Health Research Centre designed an ambitious four-cell experiment to test different models of community health and figure out which delivered the best outcomes.

Finding the right approach

Dr Koku Awoonor-Williams is the Director of the Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Division of Ghana Health Service. He is also one of the original architects of the CHPS programme. Well known in the country as a dedicated medical doctor and a district director of health services before rising to the top levels of the Ghana Health Service, he holds much of the historical knowledge of the programme. Dr Awoonor-Williams visited the initial experiment and later was the first to try implementing it in his own district of Nkwanta.

He describes the Navrongo experiment:

"In one cell nothing – let the natural consequences happen, no health worker, no volunteer, let’s see how people react when they have health emergency or calls for seeking health care. The second cell put a volunteer in the community who is trained and left them alone to take care of the health needs of the people. The third cell had a trained volunteer and a trained health nurse. The fourth just had the nurse."

The results were clear. The cell with the trained nurse and volunteer had overwhelmingly better results. This model became the foundation of the CHPS programme.

The development of Ghana’s primary health care programme was no accident. Dr Awoonor-Williams continues:

"It went through rigorous research, and that is where implementation and embedded research come in. Our primary health care system is not about treatment, the treatment is just one percent of it. It is mainly health education, health promotion, community durbars [meetings], outreach services, immunization and referral. Timely referral of those emergency cases that are beyond the scope of the Community Health Officer."

By 2000, CHPS was made national policy. By 2008, CHPS was in every region of the country.

But, while the initial CHPS experiment and testing in other districts was accompanied by the intensive involvement of researchers, its scale-up to other areas of the country did not have the same level of research support.

Finding the right approach

Dr Koku Awoonor-Williams is the Director of the Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Division of Ghana Health Service. He is also one of the original architects of the CHPS programme. Well known in the country as a dedicated medical doctor and a district director of health services before rising to the top levels of the Ghana Health Service, he holds much of the historical knowledge of the programme. Dr Awoonor-Williams visited the initial experiment and later was the first to try implementing it in his own district of Nkwanta.

He describes the Navrongo experiment:

"In one cell nothing – let the natural consequences happen, no health worker, no volunteer, let’s see how people react when they have health emergency or calls for seeking health care. The second cell put a volunteer in the community who is trained and left them alone to take care of the health needs of the people. The third cell had a trained volunteer and a trained health nurse. The fourth just had the nurse."

The results were clear. The cell with the trained nurse and volunteer had overwhelmingly better results. This model became the foundation of the CHPS programme.

The development of Ghana’s primary health care programme was no accident. Dr Awoonor-Williams continues:

"It went through rigorous research, and that is where implementation and embedded research come in. Our primary health care system is not about treatment, the treatment is just one percent of it. It is mainly health education, health promotion, community durbars [meetings], outreach services, immunization and referral. Timely referral of those emergency cases that are beyond the scope of the Community Health Officer."

By 2000, CHPS was made national policy. By 2008, CHPS was in every region of the country.

But, while the initial CHPS experiment and testing in other districts was accompanied by the intensive involvement of researchers, its scale-up to other areas of the country did not have the same level of research support.

The challenges of scaling up

Dr Ayaga Bawah heads the research arm of a programme aiming to strengthen CHPS implementation. Based at the University of Ghana he has an insider’s view of the challenges experienced, having worked at the Navrongo Health Research Centre in its early days. He says:

“That is where the problems started. The scale-up process was completely different from the Navrongo experiment, which was a very closely monitored system. Now you have a national programme. All of a sudden the entire country has been asked to take this programme and many of the actors were not part of the original design, the original implementation. They have picked bits and pieces of it and were asked from now on to implement the policy.”

For Dr Awoonor-Williams, the slow pace of scale-up was a grave disappointment.

“We commissioned a study to understand the national strategy after 15 years of implementation. Our coverage should be 90-95% coverage, but at the time we were just about 30% coverage.”

The study uncovered that there was variation in the ways that CHPS was being implemented by different districts. The vital element of community engagement was not always adequately implemented, local political will and management capacities needed to be built up and supervision and information systems were weak.

It was time to get everyone together to chart a new direction.

The challenges of scaling up

Dr Ayaga Bawah heads the research arm of a programme aiming to strengthen CHPS implementation. Based at the University of Ghana he has an insider’s view of the challenges experienced, having worked at the Navrongo Health Research Centre in its early days. He says:

“That is where the problems started. The scale-up process was completely different from the Navrongo experiment, which was a very closely monitored system. Now you have a national programme. All of a sudden the entire country has been asked to take this programme and many of the actors were not part of the original design, the original implementation. They have picked bits and pieces of it and were asked from now on to implement the policy.”

For Dr Awoonor-Williams, the slow pace of scale-up was a grave disappointment.

“We commissioned a study to understand the national strategy after 15 years of implementation. Our coverage should be 90-95% coverage, but at the time we were just about 30% coverage.”

The study uncovered that there was variation in the ways that CHPS was being implemented by different districts. The vital element of community engagement was not always adequately implemented, local political will and management capacities needed to be built up and supervision and information systems were weak.

It was time to get everyone together to chart a new direction.

Step 2

Get everyone around the table

Build a shared agenda for change. Successful embedded research projects bring everyone - researchers, implementers and policy-makers - together from the very beginning. Involving other stakeholders, such as communities and development partners can be crucial. Everyone needs to agree on the questions that are asked, the methods to be used and who will be involved.

Bumps in the road

Building a health system requires tenacity. Scaling up rarely goes smoothly – problems crop up over the course of years. It can be a long slog.

While exciting new technological innovations often hit the headlines – a novel drug, the promise of new information and communication shifts – what often makes the difference is everyone pulling together to improve existing ways of doing things, monitoring success and making small changes for the better.

The national review of CHPS was a time to take stock and to plan for the future. Plans were made to strengthen the way that CHPS was implemented by trialling new ways of supporting districts through the Ghana Essential Health Intervention Project and subsequent embedded research programmes.

Identifying and solving problems together

The Director General of Ghana Health Service, Dr Anthony Nsiah-Asare, was originally a surgeon and hospital administrator as well as working at regional level as a manager. He has held the role of Director General since 2017.

“We want to achieve Universal Health Coverage at the primary level before the year 2030. That’s our vision. We should have good accessibility near to where people are through the CHPS system.”

Embedded research requires the creation of new relationships to identify the most pressing challenges and to approach them together. It means being able to see where and why a programme is not working and enables adjustments to be made and evaluated programmes to move forward.

As Dr Bawah explains:

"The idea was just to try and fix the problems that were encountered in the course of the scale-up in Ghana. Looking at issues of documentation, making sure that the system has what it needs to be able to move – so logistics, human resources, leadership and all those were the things that we had to try and implement. What we are doing is to make sure that research becomes an integral part of the implementation process, and that is why embedded research is so critical in this process."

Step 3

Communicate regularly

Share data and intelligence as it becomes available. When research is underway, it is important to share information about what is being revealed as it happens. This allows for adjustments to a programme based on new knowledge and for researchers to respond to emerging policy or implementation priorities. Observing and reacting to new information can have real impacts for those working on the frontline of health.

Working with the community

Nkwanta South is in the east of Ghana near the Togolese border. Over 74% of the district population is rural, and most people work in agriculture, fishing and forestry. It is one of the districts where embedded research is contributing to the monitoring and scale-up of the CHPS programme. It’s the district where Ms Amenyo carries out her work as a Community Health Volunteer.

Ms Amenyo is the face of the health system in her community. She is the link person between the community and the health workers. She is a source of health information and education. Communities are a great source of material and moral support to the health workers in their midst. Ms Amenyo works closely with the nurses at her CHPS compound, like Ms Patricia Teye.

For nurses like Ms Teye, who are posted to the rural areas, the realities of delivering health care outside of a high-spec hospital setting in the capital city can be a shock:

"I was told that the place was very far and that life there was very challenging because it is very far. It is not easy getting potable water. There is no light. I remember the inauguration day, the day they were inaugurating the facility, that was the first time I went there. I had to be introduced to the community. I wept. I wept because I was just thinking how I could handle all of that."

But although village life has its challenges, Ms Teye also feels compensated by the strong relationships that she has built with the community she lives with.

“They are easy to be with when you are able to act on their challenges and sit down and solve their issues.”

Ms Teye works under the supervision of the District Health Team - who provide guidance and moral support to enable her to respond to the community’s needs. They are in close contact, despite being separated by poor roads and unreliable telephone networks.

Receiving research feedback in real time

In Nkwanta South, health services are managed and supervised by the District Health Management Team, which is overseen by Dr Laud Boateng, the District Director of Health Services. For frontline staff working in very challenging circumstances, knowing that people higher up the system have their back is important.

Thanks to the embedded research programme, Dr Boateng has experts from the University of Ghana and the University of Health and Allied Sciences (UHAS) to turn to when the programme experiences a problem. He is full of praise for the approach:

"They are giving us feedback in real time. Not at the end of the research. Not in a paper in a journal where no one has access. So, we are going through multiple iterations and changes where we are modifying our approach in service delivery or programme implementation."

Using new data to make small improvements

The regular sharing of data between the research team and Dr Boateng has led to some unanticipated benefits for CHPS, which help with everyday decision-making. For example, some asides made in initial focus group discussions organized by UHAS highlighted that lower-level staff in the health facilities felt that their supervision was too stern and not supportive.

Dr Boateng was able to swiftly address the issue, holding human resource management training on addressing conflict and conducting monitoring visits. He arranged regular football and volleyball games to get people socializing together and an official awards ceremony to celebrate the successes of staff. This has led to more transparency and confidence in staff with management responsibilities and less intimidation among those they supervised. Staff now cooperate better as a team.

Embedded research is a practical way of supporting health systems, using context specific methods, when they are experiencing difficulties.

Step 4

Think local

Research should respond to real-world challenges. Embedded research needs to respond to the problems and challenges that are being faced by policy-makers and health staff on the frontlines. Effective partnerships with local research institutions can be key to this. In Nkwanta South, the support CHPS receives from the staff at the UHAS is invaluable.

Research that reacts to local needs

Embedded research can take many forms and use different research methods. In Nkwanta South, Professor Margaret Kweku and her team from UHAS have used a participatory approach to find out what areas of CHPS community members and health staff think need improving, and then devised a staff training programme to respond to these challenges.

This research supports Community Health Officers like Ms Teye, who has received training from the UHAS team. The training addressed issues such as community entry and cultural competency, emergency delivery in the community, resuscitation of newborns and management of neonatal and childhood illnesses.

The training complements what nurses have learned in school. For Ms Teye, this was invaluable. For example, while she had assisted with deliveries at the hospital during her orientation, it was quite a different experience to being the only health care worker in the vicinity when a woman gave birth in her village and an emergency arose that needed to be dealt with immediately.

She is humble about what she learned on the job from her community:

"So the Traditional Birth Attendant was coming to the health facility with this pregnant woman in labour. The Traditional Birth Attendants know they have to bring cases to us. We don’t make them feel as if we are taking their job away from them. That is why we have to participate, assist them and encourage them."

The training has enabled the health system to incorporate community priorities into the way that services are structured while ensuring that health staff have access to up-to-the-moment clinical guidance. Whenever Traditional Birth Attendants accompany pregnant women to the nurses for delivery, they are allowed to assist and provide support in the delivery. This encourages them to continue referring women to health facilities.

Innovations at the community level mean that former Traditional Birth Attendants, like Ms Amenyo, are supporting the health system – and the results are impressive.

UHAS conduct routine evaluations of the effectiveness of the trainings within the health system using in-depth interviews and observational checklists to assess changes in practice. Focus group discussions with the community health committees and surveys with community members allow them to get a sense of the community’s perception of the changes. This information gets fed directly into decision-making so that the way services are delivered can be tweaked and adjusted.

Integrate research into the day-to-day delivery of health care

Making research relevant to real-world challenges is one of the key principles of the embedded research approach. Dr Bawah is passionate that this is an approach that pays dividends:

"I have always said that very often researchers think that they are the major repositories of knowledge. So, we tend to often operate from an ivory tower perspective. You come from academia, you go into the community, you conduct your research, report your results and you expect the policy community is going to run away with it. It doesn't work like that. We have come to realize that for adoption of research you need to work closely with the policy community."

Particularly in settings where there are limited resources, failing to include policy-makers in the design of studies can lead to waste and frustration further down the line. This kind of approach is all too common in Ghana and elsewhere.

Embedded research is not a detached academic exercise; it is a collaborative process that involves negotiation with multiple players in the health world. It also means constantly reviewing what is being done and seeing where improvements can be made.

Professor Kweku’s research is also supporting a larger adjustment to the CHPS programme: it has uncovered gaps in service provision, and this is where the programme will evolve next.

Integrate research into the

day-to-day delivery of health care

Making research relevant to real-world challenges is one of the key principles of the embedded research approach. Dr Bawah is passionate that this is an approach that pays dividends:

"I have always said that very often researchers think that they are the major repositories of knowledge. So, we tend to often operate from an ivory tower perspective. You come from academia, you go into the community, you conduct your research, report your results and you expect the policy community is going to run away with it. It doesn't work like that. We have come to realize that for adoption of research you need to work closely with the policy community."

Particularly in settings where there are limited resources, failing to include policy-makers in the design of studies can lead to waste and frustration further down the line. This kind of approach is all too common in Ghana and elsewhere.

Embedded research is not a detached academic exercise; it is a collaborative process that involves negotiation with multiple players in the health world. It also means constantly reviewing what is being done and seeing where improvements can be made.

Professor Kweku’s research is also supporting a larger adjustment to the CHPS programme: it has uncovered gaps in service provision, and this is where the programme will evolve next.

Step 5

Keep going

Always build on success. If research leads to a successful outcome, scale up. As new innovations are implemented throughout the system, challenges will emerge that throw things off track. Embedded research will help get things back on the right road.

Always adapting and improving

While CHPS was created to respond to pressing needs related to reproductive and child health, as we look to the future it is likely that new areas will be integrated into the service that is provided.

Embedded research is key to helping the CHPS programme innovate and evolve. It helps the programme learn and adapt when interventions don’t work as planned or when new health concerns arise in the community. And with each adaptation the process of embedded research continues, ensuring that new services and the policies that guide them are informed by recent evidence that comes directly from the knowledge of communities and staff working at different levels of the health system.

Professor Kweku believes that the embedded research in CHPS has helped policy-makers and health staff better understand the needs of the community and where they can work better and smarter:

"During the first evaluation, we realized that people over 30 don’t really value CHPS. The men, for instance, for them it is not their business at all because it is only mothers with children under five and those who are pregnant who are benefiting. When we started this training, I told them that this would help them expand the scope of CHPS. We are now involving everyone. Because if you can screen them for blood pressure, blood glucose and refer, at least they have gained something from you. These are some of the things we want them to add onto CHPS, and that is why we are training them at this time on these topics."

Embedded research works

Over the last 20 years, the CHPS programme has transformed the way health services are delivered in Ghana. And embedded research has been fundamental to its success.

Evidence of success

Ghana’s embedded research approach has brought together all stakeholders to support better health and well-being - from communities and frontline staff to researchers and policy-makers. It has shown which interventions will work and why. And when things are not working as expected, it has enabled Ghana’s health workers and researchers to identify the causes and find solutions.

Most importantly, Ghana’s experience shows it is an approach that other countries can benefit from. The beauty of embedded research is that it can be applied to a wide range of issues in the health system, in many different contexts. Dr Boateng is clear that others can benefit:

“This is something that should be emulated. We should do more research and disseminate this approach for others to look at as well.”

In Ghana, embedded research has prompted learning at the individual level. For Ms Teye, the training has built skills that have helped her to offer the best service possible to her community. For her, CHPS is about creating a more equitable society, where the circumstances of birth do not dictate the quality of care received.

And it is shaping the way that health care will be delivered for years to come. As part of the programme, Professor Kweku’s team at UHAS have had a chance to directly and closely engage with health workers and communities. Learning from the embedded research has enabled them to update and sharpen their teaching modules. With the help of embedded research, they are training and supporting the health workforce of the future.

But learning from embedded research also reverberates throughout the health system. These CHPS districts are pioneering tangible changes in practice that other areas in Ghana can learn from. This approach is supported at the highest level of the health system. Dr Nsiah-Asare believes that it could also provide a template for other countries to explore:

“We in Ghana believe in research embedded in policy. If anybody is listening, we believe that is the way that every country whether developed or developing should go.”

Acknowledgements

This story was produced by Fat Rat Films. It was directed by Gemma Atkinson, who also managed the project. It was produced and also developed for web by Jodie Taylor, written by Kate Hawkins, filmed and photographed by Josh Hughes and the videos were edited by Sibila Estruce. Graphic design support was provided by Chris Barry and Francis Redman. The project was overseen by Jeffrey Knezovich, who also provided technical and editorial input.

This story would not have been possible without our contributors: Elizabeth Amenyo, Norbert Attah, Dr Koku Awoonor-Williams, Dr Ayaga Bawah, Dr Laud Boateng Professor, Margaret Kweku, Dr Anthony Nsiah-Asare, Dr Anthony Ofosu, Patricia Teye and Peace Yeple.

We would like to thank the people of Nkwanta South, especially those in Salifu and Alokpatsa, for their support and participation.

We would also like to thank the community health volunteers and the community health officers who gave us their time and told us their stories, even if we couldn’t include them all.

This product is the result of the hard work and close collaboration with many in the Ghana Health Service and partners, including: Mathias Aboba, Felicia Babanawo, Esther Effah-Afari, Winnard Agbeko, Paul Angwaawie, Godwin Vidzro, Liberty Apedjah, Roland Glover, Sophia Benyigah Sorloum, Idam Johnson Bano, Millicent Ampofowa, Ms Margaret Mensah, Mrs Evelyn Mawutor Nugbey, Rabiatu Alawiye, Alhaji Moro Iddi, Diction Azumah and Andy Nelson among many others. Research partners from the University of Ghana, the University of Health and Allied Sciences and Columbia University have also helped to make this possible.

The guidance of Dr Abdul Ghaffar and support from other colleagues at the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research – including Dr Zubin Shroff, Dr Aku Kwamie and Dr Kabir Sheikh – has also been invaluable.

The Alliance is able to conduct its work thanks to the commitment and support from a variety of funders. These include our long-term core contributors from national governments and international institutions, as well as designated funding for specific projects within our current priorities. For the full list of Alliance donors, please visit: https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/partners/en/.

This project, in particular, has been made possible through the support of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (DDCF). Lola Adedokun, McKenzie Bennett and Kristin Roth-Schrefer from DDCF all provided useful feedback on the story.

Sources

Line chart: Ofosu, A., Ghana Health Service, Births in Nkwanta South attended by skilled health professional, Ghana District Health Information System (DHIMS2), unpublished data made available through personal communication, 25 April 2019.

Archive photo: ‘International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978’, © World Health Organization

All other photos and images included in this output were captured specifically for the project and are also © World Health Organization.

WHO/HIS/HSR/19.2

© World Health Organization

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncsa/3.0/igo).

Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Suggested citation. The bumpy road to better health [website]. Geneva, Switzerland: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization; 2019 (https://www.ahpsr.org/stories/the-bumpy-road-to-better-health)

Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requests for commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.

General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall WHO be liable for damages arising from its use.